Time to read: 6 min

The development of autonomous vehicle technologies, coupled with a growing demand for personal transport options and decreasing interest in vehicle ownership, is radically impacting the automotive industry. Forward-thinking OEMs* like Ford are responding with a bold new strategy: redefining themselves as service-oriented mobility companies.

We talk to Adi Singh, Research Scientist at Ford’s Silicon Valley-based Research and Innovation Center, to discuss how the Silicon Valley ecosystem is impacting Ford’s development processes, the challenges of shifting the mindset of a hundred-year-old legacy, and Ford’s transition to the mobility company of the future.

How to Shift a Mindset

Innovation has never come easy. Homo sapiens is infamous for being an animal of habit—just a few centuries ago people were burned at the stake for suggesting the Earth isn’t flat or the center of the universe. We’re thankfully past that today, but our inborn resistance to change persists. And it takes, as always, visionary minds to push the rest of us out of our comfort zone.

“A mindset is [very] hard to change,” shares Adi. “Especially when you’re talking about people who have been with the company two, three decades. It’s been an uphill battle for us to influence the established mindset. It’s almost as difficult as starting something new—if not harder. You’re not only trying to prove the value of this incredible new work you’re doing, you also need to build a bridge between the mindset of innovation and the mindset of the set-in-stone here in the Midwest.”

Perhaps ironically, it’s not just Ford’s own people the company needs to bring onboard its new ship of change.

It’s undisputed throughout the company that there’s a lot of innovation in [the Valley] and that if you’re not harnessing it, you’re missing out big time

“When we do recruitment events,” explains Adi, “we get a lot of aeronautics people even though we’re recruiting for software. It’s a self-selective crowd because of the brand and legacy everyone associates with us. No one expects us to be doing software engineering, despite the fact that cars are the ultimate systems integrator. There’s a hundred million lines of code in a Mustang. A Boeing 747 has only about eight million.”

That seems frightfully counterintuitive, but Adi explains it’s only because cars are driven by regular people, whereas planes are operated by trained pilots.

And yet, Ford’s workforce does recognize the innovative spirit of Silicon Valley. “It’s undisputed throughout the company that there’s a lot of innovation in [the Valley] and that if you’re not harnessing it, you’re missing out big time,” says Adi.

Investing in Silicon Valley

The company is acutely aware it needs to capitalize on that recognition, ASAP. One of the ways it’s doing so is through investment. The company is investing heavily in establishing a presence in Silicon Valley to accelerate the speed of development in the autonomous vehicle race—as are other OEMs like BMW, Honda, and General Motors.

“You always want to move as fast as possible,” says Adi. “So when we see another company working in an area we’re interested in, that automatically increases our own speed. Everyone feels the need to hustle.”

And Ford knows if it waits for its entire population to shift their mindset, it’ll be too late.

“Now that the landscape is changing, we’re taking a step back to see how we can influence other forms of mobility”

“We’ve made several major investments here in the Valley,” Adi tells us. With Baidu as a co-investor, Ford pumped $150 million this spring into Velodyne, one of the world’s top makers of lidar sensors (Lidar uses lasers instead of radio waves to detect objects). In July, Ford invested in Civil Maps, a Stanford StartX project, with five other investors in a round led by Yahoo! Inc. co-founder Jerry Yang. And of course there’s its new commuter shuttle service, Chariot, the first acquisition of its freshly formed subsidiary Ford Smart Mobility (more on this later). Ford is also sponsoring Bay Area Bikeshare.

Mobility Re-defined

New visions and new strategies require not just new mindsets but entire new approaches, to everything from design to engineering to marketing.

But first, let’s define this whole “mobility” thing. Already on the verge of becoming one of those overused but under-valued buzzwords, mobility refers to, in Adi’s words, “anything involved in moving people and things from point A to point B.”

“Ford has always been a mobility company, although primarily for the single occupant,” he says. “But now that the landscape is changing, we’re taking a step back to see how we can influence other forms of mobility, our new shuttle for example. We’re also looking into bikes, shared parking, even shared driving.”

Shared vehicles, of course, go against the very grain of the traditional automotive business model, which calls for every American to have at least a few cars in their garage. But, as we’ve said, the world is changing, and our beloved car companies are changing along with it.

“Our legacy processes were streamlined for designing and producing cars, not for being a user- and design-focused tech firm”

When you design a single-occupancy vehicle, your entire focus is on that single occupant operating that vehicle, explains Adi. But when you’re designing a vehicle for multiple drivers and riders, your focus opens up significantly. “You need to understand the dynamics of public transportation. How it fits with the infrastructure of a city. Its culture. Its economy. All of these factors affect the design of the product.”

A New Focus on User Experience

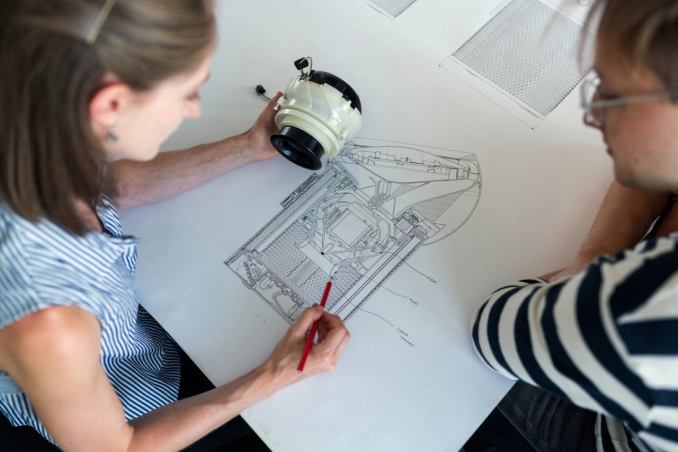

First, Ford evolved its entire design process and thinking. The latest commuter shuttle design, shares Adi, is “the result of a two-year study we did with IDEO. We made cardboard prototypes. We made models of different seat layouts, using a simple wooden board placed at different heights to test optimal heights. Other wooden boards tested different door operations. We can easily fill a shuttle with 14 seats, but the question we asked was, what’s the user experience in those 14 seats? People want more legroom and they want USB access. And we’re gathering [user] feedback through our mobile app. This is the type of design thinking that’s permeating our mobility business now.”

Secondly, from a process/logistics standpoint, Ford’s customers have always been the dealers, not the end-users. Following in Tesla’s footsteps, Ford now needs to learn how to interface directly with the people driving—or riding in—its vehicles.

Third is that tricky issue of autonomy. As in, a vehicle that drives itself, and takes the driver out of the equation. Adi asks the rhetorical question countless other automotive executives and engineers are also posing: “How do you get people comfortable with the idea of autonomy?”

“These are all the things we’re debating now. Getting the technology ready is just one part of the solution. The biggest part is user acceptance.”

The Case for Flat Hierarchy

When innovating, it’s always a good idea to set up a brand new entity. In March of this year Ford announced the formation of Ford Smart Mobility (FSM), a new subsidiary whose goal is to “design, build, grow and invest in emerging mobility services.”

Adi says that “we did that because we recognized our [legacy] processes were streamlined for designing and producing cars, not for being a user- and design-focused tech firm. The main difference between ‘big Ford’ and FSM is that FSM has a nearly flat hierarchy. That does away with all that red tape that’s still useful today in car manufacturing, but not for [the autonomous vehicle] industry. For example, big Ford requires multiple reviews before any new thing, any part or process, can be approved. When you have hundreds of projects, that kind of review process becomes overwhelming.”

FSM, in other words, is revving up its development speed by slashing bureaucracy. Not a bad thing, certainly.

“In a services-oriented design process,” Adi adds, “the sign-offs are more localized. There is a lot of freedom and flexibility in terms of the avenues we’re allowed to explore. So if we have five talented people working on a problem, they should have the freedom to just do it instead of having to work through a bottleneck.”

Will It All Pay Off?

All of the effort, energy and resources that Ford and other automotive manufacturers are pouring into this new world of mobility are substantial and worthy of following closely. But two large questions remain: user acceptance and a sustainable business model. With something as personal, ubiquitous, and safety-related as automotive transport, many pegs will need to fall into all the right places before we can say that this industry has been truly transformed.

*OEM = original equipment manufacturer

– – –